Introduction

This paper is made up of two interconnected sections. The first part concerns itself with an analysis of the key features of qualitative research and in order to arrive at a conclusion about the contribution that qualitative research has made to educational research a number of underlying principles and assumptions are clarified. A structure based upon the ontological, epistemological and methodological assumptions that underlie the interpretivist approach as outlined by Cohen et al (2011) and an overview of qualitative inquiry’s development over time as proposed by Denzin & Lincoln (2011) will be provided. A brief outline of the key differences to be found between deductive and inductive reasoning will be addressed and comparison with post positivist concepts will help to define clearly, the interpretivist position in question.

Firstly, nursing has always had a distinctively subjective point of view in contrast to its medical colleagues who have been characterised as being epidemiologically focussed. Thus, it follows that a research methodology that lends itself to the illumination of the individual’s perspective in a given context will attract those that hold this view anyway, (Leninger 1985). This position is supported by Parahoo (2006 p. 73) who points out that if nurses are concerned with including patients in decisions about their care then they must know what their view is. To best facilitate this insight then qualitative methods would seem to offer the best fit in terms of method.

Having considered the components and development of qualitative research; consideration is given to the impact that qualitative research has made in education in general and in the education of nurses in particular. This will be facilitated by critically analysing three papers from the area of nurse education with a view to determining how they were designed, conducted and contributed to knowledge and/or practice in terms of the conclusions drawn. The analysis of the papers will be viewed in the context of healthcare being driven by evidence based practice. Nursing research is expected to produce research outputs that can be used to develop or modify practice or at least contribute to a growing body of knowledge that enables practice to be developed effectively (Parahoo 2006). Analysis of the papers will attempt to identify if the premises identified in the early part of the assignment are apparent in the study designs and thus contribute to their credibility or truth value. This should therefore illuminate the extent to which the findings and conclusions could be used to either generate a cogent theory that might explain phenomena beyond the immediate sample or provide evidence to justify (in part) practice development that impacts on culture and other esoteric concepts (Boomer & McCormack 2010).

The three papers selected for analysis are clearly are based in the interpretivist paradigm and have used a qualitative method to generate data, carry out analysis and draw conclusions. The papers are; Empowerment and being valued: A phenomenological study of nursing students’ experience of clinical practice, (Bradbury-Jones, Sambrook & Irvine 2011). Judgements about mentoring relationships in nurse education, (Webb & Shakespeare, 2008). An interpretive study of the nurse teacher’s role in practice placement areas, (Duffy & Watson 2001). The first paper is a self-titled phenomenological study, (Bradbury-Jones et al 2010) and a qualitative approach is apparent when they describe their motivation for including students as getting their view and justify this by pointing out that this, (the student experience) has been excluded in the literature. The paper by Bradbury Jones et al (2011) is clearly set within the interpretivist paradigm and clearly specifies the approach taken to the study by specifying that it is a phenomenological study. The paper by Webb & Shakespeare (2008); Judgements about mentoring relationships in nurse education, in a similar fashion to Bradbury-Jones et al (2010), advertises its interpretive credentials in its title by identifying judgement and relationships as the focus of its inquiry. The aim of Webb & Shakespeare’s (2008 p.564) study was, “to explore how mentors make judgements about the clinical competence of pre-registration nursing students”. The point to note in the aim is the use of the word how that demonstrates a focus upon process that would be in keeping with qualitative inquiry. The third paper chosen was by Duffy & Watson (2001), who carried out a study to explore the role of nurse teachers in the clinical area. They pointed out that this had been investigated previously but they were motivated by providing a Scottish context that had been missing from the literature. The study occupied the interpretive paradigm and was concerned with investigating the life worlds of nurse lecturers and their perceptions of their role in clinical practice. This is an issue that continues to occupy the mind of nurse education. The papers were chosen to demonstrate the value of a qualitative method in education in nursing that that would facilitate change at a local level through practice development (McCormack & Manley 2004).

In the first instance the philosophical basis of qualitative research will need to be addressed. The philosophical basis of qualitative research and indeed all research may be subdivided into its ontology and epistemology. This sets the parameters of methodology and guides research method (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2011 p. 3). It also affects how data are collected and analysed and ultimately influences their use afterwards.

Ontology is described by Powers and Knapp (1995) as the study of the nature of reality and Corbin & Strauss (2008 p. 6-8) point out eighteen assumptions that underpin the interpretive view. An ontological position enables a researcher to lay the foundations of their position in relation to research design and Corbin & Strauss (2008) note that qualitative research is underpinned by interactionism and pragmatism. The paradigm is generally known as the interpretivist paradigm; that ontologically assumes that the world as one sees it, is a subjective interpretation of sensory stimuli that are continuously changing, (albeit subtly). This leads to the claim that there is no one objective external reality that can be definitively measured. This position is arrived at by claiming that sensory input are being interpreted by the individual to enable them to make sense of it or construct meaning. Added to this, interpretivism would also highlight that external reality is also affected by other people; thus the interpretivist view would be that the world as perceived and interpreted is socially constructed. This leads to a position where individuals exist in a world of multiple realities, (Silverman 2011 p.293).

On the other hand, the post positivist paradigm according to Polit & Beck (2012) assumes that there is an external objective reality that is independent of our thinking and that can be observed and thus measured. Okasha, (2002), referred to this as realism; the world exists externally and independently of the individual. Cohen et al, (2011) listed this as being positivisms key ontological feature. In its simplest form, quantitative research seeks to reduce the phenomena to be studied or measured to variables in order to produce proof and consequently make predictions about the world, (Burns 2000.). The paradigm tries to exclude or at least minimise the effect of other or confounding variables in order to attribute any recorded change to the variable under investigation. In this regard the quantitative approach to science aspires to being value free and neutral and thus claims any observed change to be free from bias and therefore must be accepted as the truth. Positivism as an umbrella term contains several subdivisions that are subtly differentiated from one another. These were described by Hartas, (2010) as classical positivism, logical positivism and post positivism and developed over time.

Building up from an ontological base, epistemology is the study of knowledge and how it is acquired and or constructed (Powers & Knapp 1995). Following on from the ontological position described above then, the interpretivist view of epistemology would be that knowledge is constructed by the individual after experience/perception of it. The important point here is that the interpretivist acknowledges that it is the interpretation of perception of sensation that produces experience and that pure sensation would not be experience at all, (Merleau-Ponty 2002)

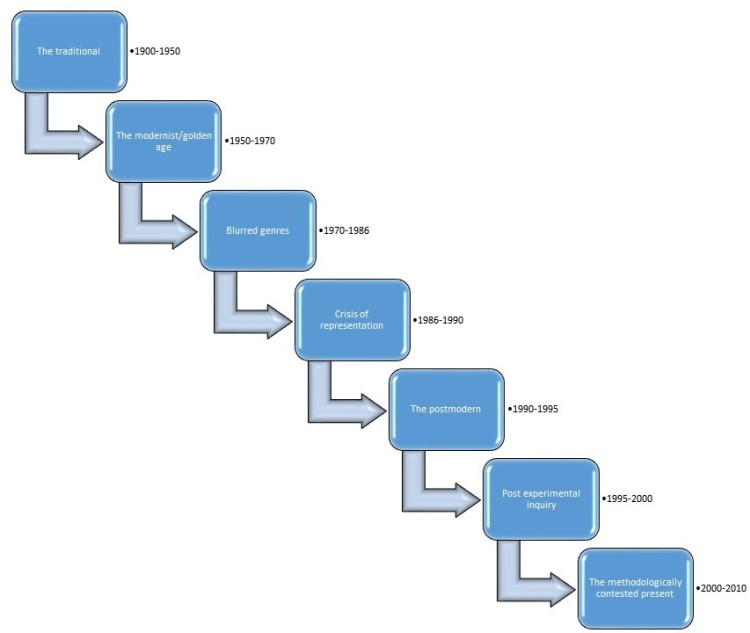

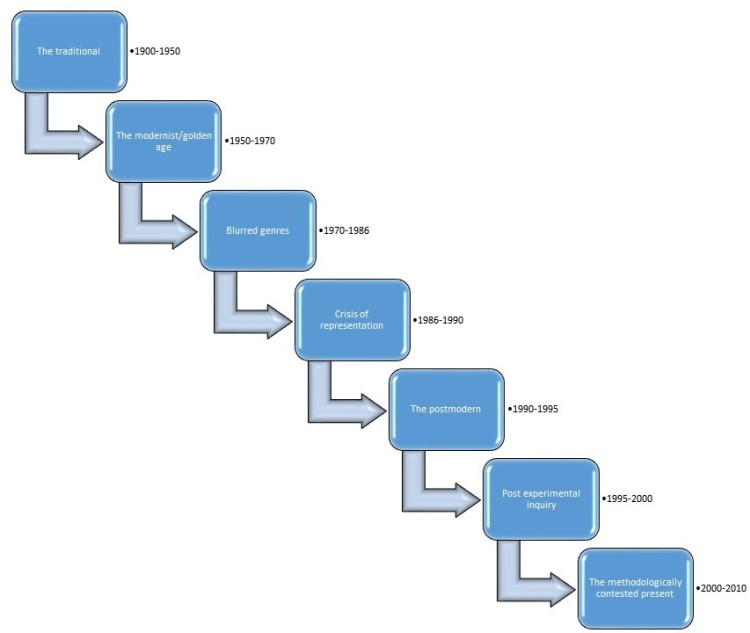

Having considered the ontological and epistemological foundations in interpretivist research the focus moves onto methodology and method. Methods in qualitative research have developed over time and Denzin & Lincoln (2008) assert that there have been eight distinct or overt moments of qualitative research development although they concede that there may have been more. In addition to this Denzin and Lincoln (2011) qualify their moment’s model by highlighting that they are aware that it is an artificial construct that has subdivisions that overlap and are still in effect in the present day. To that end the model may be described as a crude unidirectional aide memoir to enable the reader to discern qualitative research development over time.

They highlight that qualitative research is a relatively recent development in terms of research overall and suggest that the first moment is, the traditional, ranging from 1900-1950. At this time they argue, research was characterised chiefly by positivist philosophy and was dominated by quantitative designs. Anything else was considered to be not research. Following philosophical development however, qualitative research went through a period of identification concerned with differentiating itself from positivist research and locating is own philosophy and methodology. This second moment from 1950-1970 is called the modernist or golden age and contained the genesis of a variety of methods suited to conducting qualitative research. The rush of qualitative method development gave rise to cross pollination and this denoted the third moment defined as blurred genres (1970-1986). At this point it was suggested that a popular characteristic of the qualitative researcher was one of being a bricoleur, (Willis 2007). Denzin & Lincoln (2008) described a bricoleur as one who was able to be methodologically versatile and draw upon a range of methods to answer context specific questions. They caution however, that such borrowing runs the risk of compromising methodological integrity and consequently, the next moment is defined as Crisis of representation, (1986-1990). Willis (2007) describes this as a time when qualitative research realised that there was no universal truth to be discovered and that data collection and data analysis were not separate activities. This period also saw a rise in the importance of reflexivity. The fifth moment labelled the postmodern (1990-1995), is characterised as being a time when the separation between the researcher and the researched became blurred and an emphasis on story-telling arose. The sixth moment, post experimental inquiry (1995-2000), saw the development of a variety of creatively based methods of inquiry and reporting such as drama, conversation and performance. The methodologically contested present (2000-2010) is described by Denzin & Lincoln (2008) as the moment when multiple interpretive practices co-exist but Willis (2007) pointed out that this moment is also characterised by conflict arising from deciding upon criteria for publishing due to the development of a number of qualitative journals seeking criteria to set for publication. The future (2010-present), is labelled by Willis as methodological backlash and highlights the political context of qualitative enquiry and suggest that this period has seen the re-emergence of the primacy of post positivist type research. It is important to note though that each moment is not over or consigned to history. Each one still exerts influence and Denzin & Lincoln (2008 p.27) call this “an embarrassment of choice” in qualitative research that underscores the importance of clarity of choice when engaging in qualitative research.

They highlight that qualitative research is a relatively recent development in terms of research overall and suggest that the first moment is, the traditional, ranging from 1900-1950. At this time they argue, research was characterised chiefly by positivist philosophy and was dominated by quantitative designs. Anything else was considered to be not research. Following philosophical development however, qualitative research went through a period of identification concerned with differentiating itself from positivist research and locating is own philosophy and methodology. This second moment from 1950-1970 is called the modernist or golden age and contained the genesis of a variety of methods suited to conducting qualitative research. The rush of qualitative method development gave rise to cross pollination and this denoted the third moment defined as blurred genres (1970-1986). At this point it was suggested that a popular characteristic of the qualitative researcher was one of being a bricoleur, (Willis 2007). Denzin & Lincoln (2008) described a bricoleur as one who was able to be methodologically versatile and draw upon a range of methods to answer context specific questions. They caution however, that such borrowing runs the risk of compromising methodological integrity and consequently, the next moment is defined as Crisis of representation, (1986-1990). Willis (2007) describes this as a time when qualitative research realised that there was no universal truth to be discovered and that data collection and data analysis were not separate activities. This period also saw a rise in the importance of reflexivity. The fifth moment labelled the postmodern (1990-1995), is characterised as being a time when the separation between the researcher and the researched became blurred and an emphasis on story-telling arose. The sixth moment, post experimental inquiry (1995-2000), saw the development of a variety of creatively based methods of inquiry and reporting such as drama, conversation and performance. The methodologically contested present (2000-2010) is described by Denzin & Lincoln (2008) as the moment when multiple interpretive practices co-exist but Willis (2007) pointed out that this moment is also characterised by conflict arising from deciding upon criteria for publishing due to the development of a number of qualitative journals seeking criteria to set for publication. The future (2010-present), is labelled by Willis as methodological backlash and highlights the political context of qualitative enquiry and suggest that this period has seen the re-emergence of the primacy of post positivist type research. It is important to note though that each moment is not over or consigned to history. Each one still exerts influence and Denzin & Lincoln (2008 p.27) call this “an embarrassment of choice” in qualitative research that underscores the importance of clarity of choice when engaging in qualitative research.

Adler & Adler (1987) provided interesting insight when they summed up the development of ethnography over time as a struggle between the subjective and the objective.

Thus far it has been shown that the interpretivist paradigm is concerned with understanding the experience of the individual (or their interpretation and articulation of it). In order to elicit this and understand it, several approaches have emerged over time each with their own distinct underpinning theory. These approaches have been categorised by Creswell (2013) as narrative research, phenomenology, grounded research, ethnography and case study. However typologies are not exhaustive and Silverman (2011) offers an alternative and suggests that the main subdivisions or types of inquiry are observation, text, interview/focus groups, talk and visual data. This would appear to take a more process or method driven approach as opposed to Creswell (2013) who takes a more theory driven approach. This highlights the potential for confusion that may exist in qualitative research and exemplifies the idea that qualitative inquiry takes place within a dynamic system.

Narrative research was defined by Creswell (2013) as a study of experience as expressed by individuals. The narrative can be collected by the researcher or an autoethnographic approach can be taken whereby the participant records their own story. The three papers selected for inclusion in this assignment show that each study could possibly be classified as narrative and thus some confusion may arise given the overlap that exists between methods. However, Creswell (2013), offsets this somewhat by providing a table that delineates between approaches when designing the architecture of one’s study.

Phenomenology as a methodological approach to qualitative inquiry stemmed from the philosophy of phenomenology and is concerned with the lived experience of individuals. Hermeneutic phenomenology is influenced by Van Manen (1990) and concerns itself with experience as lived as opposed to conceptualised. This demonstrates its phenomenological roots as Husserl suggested that phenomenology was an attempt to return to the essence of the things themselves. This approach is seen overtly in the paper by Bradbury-Jones et al (2011), who clearly described the rationale for using such an approach to uncover or get at the experience that the participants in their study had.

Grounded theory as the name suggests attempts to generate theory that is derived from the data that has been generated from the ground up. This approach necessitates the setting aside of theoretical frameworks and allows themes to emerge from the data that are continuously in flux as the study progresses.

Ethnographic research is described by Creswell (2013) as an approach used to study a complete group and is useful for exploring or uncovering cultural and social norms. Adler and Adler (1987) support this and advocate the importance of observational research that promotes an intuitive familiarity with the group being studied. With this in mind then it can be seen that the study by Duffy & Watson (2001) could have benefitted from such an approach.

Case study research examines particular cases that can be bounded by time or place. This type of research uses a variety of methods and highlights the importance of context.

Added to this there are two other choices to consider when using research in education in healthcare. The first is action research as described by McNiff (2013) as a practically orientated method for solving immediate problems or reflecting on one’s practice in teaching. Action research is characterised by taking place in cycles that take the form of action plans that are focussed and manageable. The output from one cycle informs the development of the next and thus action research is seen as a continuous cycle of improvement as opposed to a one-off activity. Although action research may contain methods that would not be considered as qualitative, such as surveys, the underpinning philosophy is one of reflection and construction of meaning thus placing it firmly in the interpretivist paradigm (Cohen et al 2001). In addition action research is seen as being underwritten by critical theory insofar as it sets out to change practice explicitly (Marshall & Rossman (1999).

The second choice is Newell & Burnard’s (2011) pragmatic approach to qualitative data analysis. This approach attempts to provide novice researchers with a framework to analyse qualitative data and is based on a grounded theory approach to thematic content analysis. With this in mind though it is difficult to classify Webb & Shakespeare because the design of the study was described as qualitative but no additional information was offered to elucidate what that consisted of other than to say that it had been influenced by previous work about expert nurses. This raises questions of rigour and throws doubt on the interview guide designed for the study and has a ripple effect throughout.

Embarrassment of choice notwithstanding it is clear that in terms of method qualitative research is broadly recognised as having several key features that Patton (2002) has grouped under the headings of design, data collection and analysis. In terms of design qualitative research study is naturalistic insofar as it attempts to study the participants in their own context (Patton 2002). Each of the exemplar papers selected here claimed to have a design that studied the participants in the context of their own environment. Cohen et al (2011) support this position and point out that this is the stage of the research that locates the field of study and is characterised by the researcher being in situ. They do however, point out that the converse may be true also whereby the field of study may be located by the purpose of the study or its need. This demonstrates that the design of a qualitative study is emergent or iterative because it is flexible and has the capacity to respond to developments as they arise. Patton (2002) calls this an openness to adaptation because of deepening understanding on the part of the researcher. Purposeful sampling typifies qualitative inquiry and Patton (2002) suggests that participants are selected based on their insights into the phenomenon under investigation. To illustrate this, Bradbury-Jones et al’s (2011) sampling procedure is described as being purposeful and is in keeping with the sampling strategy identified by Cohen et al (2011) above as it choose participants who could reasonably be expected to have had the experience the authors were investigating . From a practical point of view and for the purpose of contributing to rigour inclusion criteria and recruitment procedures were described. In positivist research sampling takes place in terms of pre-selected criteria and attempts to represent a larger group, focusing on particular traits and thus reducing phenomena to variables that can be controlled and/or manipulated (Polit & Beck 2011). On the other hand in qualitative research sampling is less clear insofar as it attempts to acknowledge the complexity of people situated in a multitude of life worlds and the influence of the researcher themselves. Cohen et al (2011) describe a plethora of approaches to sampling in qualitative research. Parahoo (2006 p.273) sums this up by stating that sampling in qualitative research can be either purposive or theoretical but claims that eventually all sampling is selective and this position is supported by Silverman (2000). Duffy & Watson (2001) employed purposive sampling to target nurse lecturers but Webb & Shakespeare’s (2008) sample was described as convenience by the authors and this is in keeping with Cohen et al’s (2011) description of sampling but the paper goes on to suggest that the sample was subdivided to enable comparisons to be drawn which may not be congruent with a qualitative approach that could be evidence of the methodological compromise alluded to by Brown (2010) . In addition the paper suggests that the convenient nature and sample size were limitations despite these being hallmarks of qualitative inquiry.

Cohen et al (2011), suggest that the next stage of qualitative inquiry is a determination of the ethical issues that may arise. They point out that an overriding concern is that of informed consent but concede that the more a participant knows about a research study the more they might modify their responses. Bradbury-Jones et al (2011) were aware of the potential ethical issues that could arise in the context of their study and identified a power differential between the researcher and the participant as the researcher occupied a dual role as lecturer in the college that the students were attending. Any negative effects that this differential might produce were anticipated and steps were taken to ameliorate it. Webb & Shakespeare (2008) addressed the ethical issues in their study by describing the research governance process that was observed. Despite a dearth of information however, one cannot speculate that these were not considered. Similarly Duffy & Watson (2001) described the research governance mechanisms observed but they did however, note that informed consent and confidentiality were addressed.

In terms of data collection, qualitative inquiry tends to use the methods listed by Silverman (2011) above and Patton (2002) points out that the goal is to produce a thick description to provide insight. Thick description is described by Holloway (1997) as a detailed account that clarifies the experience of the individual and the context that it was set in. This is supported by Polit & Beck (2006 p.511) who also contrast thick with thin description that is seen as a superficial account that doesn’t illuminate the phenomenon under investigation. Qualitative data collection involves personal contact between the researched and the researcher (Patton 2002) and the experience of this feeds into the analysis of the data as it proceeds. As part of this then Patton recommends that the qualitative researcher needs to have an empathetic stance and this can be seen in the paper by Bradbury-Jones et al (2011) when they describe how they felt compelled to provide support for their participants. Bradbury-Jones (2011) appropriately link this to the stated aim of understanding student nurses experience in practice learning areas. The study seeks to understand student perceptions of empowerment and this clearly would not be something that could easily be measured in a quantitative manner thus a qualitative approach is justified. Combined with this Patton (2002) suggests that qualitative research takes place in dynamic systems that are changing regardless of the approach taken. When it comes to analysis Patton (2002 p.41) highlights five analysis strategies such as unique case orientation, inductive analysis and creative synthesis, holistic perspective, context sensitivity and voice, perspective and reflexivity.

That Patton (2002) cites inductive analysis is relevant insofar as it refers to inductive reasoning which is at the heart of qualitative research. Induction and deduction are the major ways of reasoning an argument. Inductive reasoning has been described as a process of moving from specific observation to general rule, whereas deductive reasoning moves from general principles to specific predictions, (Polit & Beck 2012). This has a number of implications for research enquiry and forms the basis of how studies are conducted. Using an inductive approach it is possible to see how one could make specific observations in a particular case and then move to a position where a general theory could be proposed. On the other hand using a deductive approach would lead to the situation where a hypothesis is proposed and subsequent observation and measurement leads the researcher to accept or reject it. Okasha (2005) described this as premises leading to conclusions; if the premises are true then it follows that the conclusion must be true also. This is an example of syllogism according to Cohen et al (2011) and may be described as a formal logic, Aristotelian form of argument. Cohen et al, (2011) went on to point out though that people also use a third way of reasoning that consists of a combination of both induction and deduction. This would enable researchers to move between theory generation and theory testing.

Primacy of data is a phrase used to denote the position that data occupies in a qualitative study. All of the conclusions drawn must be justifiable in terms of their presence in the data. A theoretical framework is not used to frame the data in advance, rather a theoretical framework may arise from the data after the fact. The questions framed to conduct a qualitative research inquiry are recognisable by their structure that seeks to interrogate process as opposed to lead to measurement. Thus qualitative questions will be framed in terms of how or why instead of by how much. Bradbury-Jones et al (2011) demonstrate this by using a method to collect data that is described as hermeneutic phenomenological and influenced by Van Manen (1997) and adherence to this method is justified by explaining to the reader that the study focus was on the students’ interpretation of their experience as they lived it as opposed to describing it. Data were gathered using one to one interviews with participants to enable them to tell their story or relate their experience.

Having obtained approval/permission; once the study begins the qualitative researcher becomes immersed in the life world of the participant and immersed in the data once it is generated. This purposively elicits ideas of being surrounded by the data as opposed to keeping it at arm’s length and further supports the idea of an emic perspective (Morse & Field 1996). This leads to the idea of a qualitative inquiry being set within an emic perspective. This is a term used to describe the point of view of the insider and may be contrasted with the term etic, which describes the observers perspective, (Holloway 1997). The emic perspective is underpinned by the concept of verstehen and is a term used to differentiate the interpretation of the researched from that of the researcher (Hennick, Hutter & Bailey 2011).

Bradbury-Jones et al (2011) described their data collection and analysis in detail and included information about how the researcher’s interpretation of the data evolved over time that demonstrated insight into a reflexive dynamic qualitative method. The results from the study were presented as three main themes that in combination made up the concept of empowerment. The themes were being valued as a learner, being valued as a team member and being valued as a person. Each theme was described briefly and a number of participant quotes were employed to convey to the reader how the theme label had been arrived at. Following presentation of results, the themes were discussed in the context of extant literature an argument was constructed that justified the researchers position and decisions. Webb & Shakespeare’s (2008) description of data collection is problematic because it would appear to be describing a mix of interviews, focus groups and telephone interviews that were arranged in response to locally arising conditions and were not part of a strategy. The authors claim that this was a strength and indeed may be evidence of adaptation and highlights the inherent difficulty associated with engaging with participants in their own environment. Data analysis was described as thematic but no framework to structure the analysis was explained. The themes that were extracted from the data referred to the attributes of mentors and students and the relationship that existed between the two. The final theme was labelled making a judgement and the authors suggested that it was dependent upon elements of the previous themes combining to inform judgements that mentors made about students. They argued that judgements about personality based on quality of the relationship between the student and their mentor was the key factor in making decisions about competence. The implication was that mentors scored people they liked more highly than those they did not. This is a notion that would lend itself to quantitative inquiry and perhaps would form the basis of a mixed methods inquiry that could investigate several facets of this concurrently or consecutively. Duffy & Watson (2001) analysed the data from their focus groups using a pre-existing and known framework that would lend rigour to the analysis. Three patterns containing a total of nine themes were proposed but only the first five themes were discussed with the remainder presented in another paper. Description of method is important in qualitative research because of the diverse contexts and detailed description feeds into the rigour of the study that in turn supports the credibility of the findings (Cohen et al 2011). This is particularly relevant when considering the concept of generalisability. Polit & Beck (2012) define generalisability as the capacity to transfer research findings beyond the study group to a larger population and this is largely attributed to quantitative research. Silverman, (2011), however has argued that generalisation should not be discounted completely in qualitative research as it may be possible and appropriate albeit with different ontological and epistemological reasons. Similarly, the positivist interpretation of reliability as replicability has no relevance axiologically to the interpretivist or interpretivist research. Positivist research seeks to control the impact that variables not under investigation have on an experiment and thus assure conditions of objectivity and neutrality. Conversely interpretivist research acknowledges the difficulty inherent in such an approach and accepts the impact of the context that an individual finds themselves in. Indeed it is context that lends credibility to interpretivist work as it allows the reader to understand the world view of the researched and a description of how the worldview of the researcher impacted upon the analysis of data enables the reader to weigh up the truth value of analysis and/or conclusions drawn.

In terms of conclusions, Bradbury Jones et al (2010) argued that insight into what constituted empowerment for student nurses would enable the profession to take relatively simple steps to facilitate this. Implementation of such action they posited would reduce risk of those students developing into nurses who could not support people in their care. The simple actions recommended are not described however, and the prospective risk warning seems somewhat tenuous. In addition it does not seem to be directly traceable back to the data so would seem to exceed the mandate proposed for phenomenologically based research as described by Van Manen (1997) and doesn’t uphold the primacy of data as described by Cohen et al (2011). Webb & Shakespeare’s (2008) conclusions seemed to be drawn chiefly from the literature as opposed to the data and thus lose their credibility somewhat whereas Duffy & Watson (2001), conclude that their findings whilst not being definitive do at least develop what they view as an ongoing argument and provide illumination.

Overall qualitative research has the capacity to address issues that affect individuals and illuminate their distinct interpretation of the experience of selected phenomena. Bradbury- Jones et al (2011) demonstrated this in their paper and clearly gave a voice to nursing students. Generating and compiling such insights enables researchers to clearly articulate the motivations underpinning actions and thus explain how a particular set of circumstances may have arisen. Webb & Shakespeare (2008) demonstrated this by using a qualitative approach to unpack the underlying components of decision making in mentorship thus enabling future development. This also has a certain predictive value but caution is urged as qualitative findings are context dependent. Duffy & Watson (2001) highlighted this when they stated that their study had been designed to investigate a particular context but also named this as a limitation of their study as they could not advocate transferability. Ultimately, qualitative research has the potential to deepen an individual’s insight into selected phenomena and thus modify how they engage with it.

Qualitative research has developed over time as shown above and will continue to do so. Corbin & Strauss (2008) argue that knowledge of ontology and epistemology is vital to the design of research (regardless of paradigm) so that one can adequately understand the rationale for the design and subsequently appropriately interpret and perhaps implement findings. Qualitative research has contributed vital insight into the motivations that underlie the actions seen by the participants in the three papers analysed and thus provides an indispensable tool for knowledge generation.

References

Adler P.A. & Adler P. 1987. The past and future of ethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 16. 4. 4 – 23.

Boomer C & McCormack B. (2010). Creating the conditions for growth: a collaborative practice development programme for clinical nurse leaders. Journal of Nursing Management. 18. 633-644.

Bradbury-Jones C. Sambrook S. & Irvine F. (2011). Empowerment and being valued: A phenomenological study of nursing students’ experiences of clinical practice. Nurse Education Today. 31. 368-372.

Brown A.P. 2010. Qualitative method and compromise in applied social research. Qualitative Research. 10. 229 -248.

Cohen L. Manion L. & Morrison K. (2011 7th edn). Research methods in Education. Abingdon. Routledge.

Corbin J. & Strauss A. (2008 3rd edn). Basics of Qualitative Research. London. Sage.

Creswell J.W. (2013 3rd edn). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches. Los Angeles. Sage.

Denzin N.K. & Lincoln Y.S. (Eds). (2008 3rd edn). The Landscape of Qualitative Research. London Sage

Denzin N.K. & Lincoln Y.S. (Eds). (2011 4th edn). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. London. Sage.

Duffy K. & Watson H.E. (2001). An interpretive study of the nurse teacher’s role in practice placement areas. Nurse Education Today. 21. 551-558.

Hartas D. (Ed). (2010). Educational Research and Inquiry. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. London. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Hennick M. Hutter I & Bailey A. (2011). Qualitative Research Methods. London. Sage

Holloway I. & Wheeler S. (1996). Qualitative Research for Nurses. Oxford. Blackwell Science Ltd.

Holloway I. (1997). Basic Concepts for Qualitative Research. Oxford. Blackwell Science Ltd.

Leninger M. (Ed). (1985). Qualitative Research methods in Nursing. New York. Grune and Stratton.

Marshall C. & Rossman G.B. (1999 3rd edn). Designing Qualitative Research. London. Sage

McCormack B & Manley K. (2004). Evaluating practice developments in: McCormack B, Manley K & Garbett R. (Eds). (2004). Practice Development in Nursing. Oxford. Blackwell Publishing.

McNiff J. (2013 3rd edn). Action Research: Principles and Practice. Abingdon. Routledge

Merleau-Ponty M. (2002). Phenomenology of Perception. London. Routledge

Morse J.M. & Field P.A. (1996 2nd edn). Nursing Research. The application of qualitative approaches. London. Chapman & Hall.

Newell R. & Burnard P. (2001). A pragmatic approach to qualitative data analysis in Newell R. & Burnard P. (2001 2nd edn). Research for Evidence Based Healthcare. London Sage.

Okasha S. 2002. Philosophy of Science, A very short introduction. Oxford. Oxford Paperbacks.

Parahoo K. (2006 2nd edn). Nursing Research. Principles, Process and Issues. Basingstoke. Palgrave Macmillan.

Patton M.Q. (2002 3rd edn). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. London. Sage

Polit D.F. & Beck C.T. (2006 6th edn). Essentials of Nursing Research. Methods, Appraisal and Utilization. Philadelphia. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Polit D.F. & Beck C.T. (2011 9th edn). Nursing Research. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Philadelphia. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Powers B.A. & Knapp T.R. (1995 2nd edn). A Dictionary of Nursing Theory and Research. London. Sage.

Silverman D. (Ed). (2011 3rd edn). Qualitative Research. Los Angeles. Sage

Van Manen M. (1990). Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Albany. SUNY Press

Webb C. & Shakespeare P. (2008). Judgements about mentoring relationships in nurse education. Nurse Education Today. 28. 563-571.

Willis J.W. (2007). Foundations of Qualitative Research. Interpretive and Critical Approaches. London. Sage

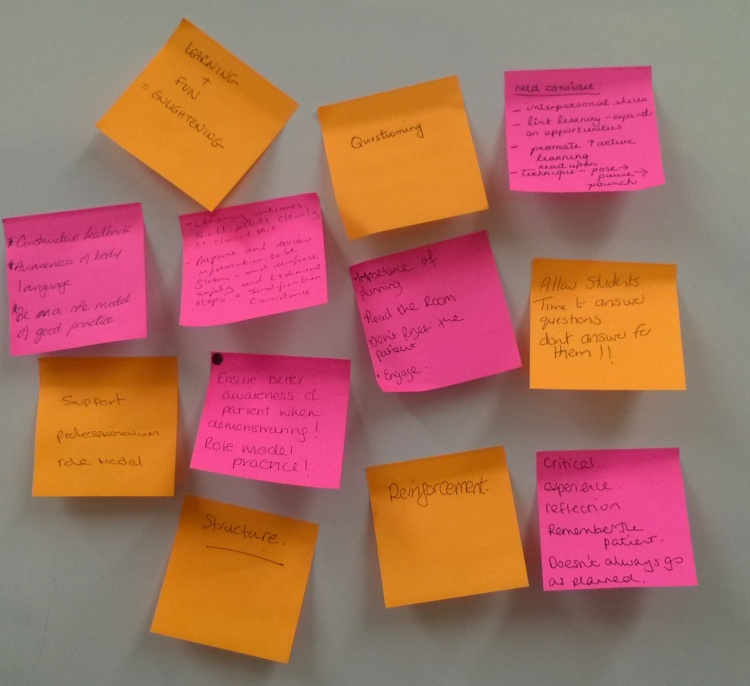

Jim Dale competent or not at I.M. injection?

Jim Dale competent or not at I.M. injection?

Using adult learning theory, (where adults are self directed and learn best when enabled to set their own learning outcomes), can create hidden tensions when the curriculum is professionally regulated.

Using adult learning theory, (where adults are self directed and learn best when enabled to set their own learning outcomes), can create hidden tensions when the curriculum is professionally regulated. Jim Dale competent or not at I.M. injection?

Jim Dale competent or not at I.M. injection?

They highlight that qualitative research is a relatively recent development in terms of research overall and suggest that the first moment is, the traditional, ranging from 1900-1950. At this time they argue, research was characterised chiefly by positivist philosophy and was dominated by quantitative designs. Anything else was considered to be not research. Following philosophical development however, qualitative research went through a period of identification concerned with differentiating itself from positivist research and locating is own philosophy and methodology. This second moment from 1950-1970 is called the modernist or golden age and contained the genesis of a variety of methods suited to conducting qualitative research. The rush of qualitative method development gave rise to cross pollination and this denoted the third moment defined as blurred genres (1970-1986). At this point it was suggested that a popular characteristic of the qualitative researcher was one of being a bricoleur, (Willis 2007). Denzin & Lincoln (2008) described a bricoleur as one who was able to be methodologically versatile and draw upon a range of methods to answer context specific questions. They caution however, that such borrowing runs the risk of compromising methodological integrity and consequently, the next moment is defined as Crisis of representation, (1986-1990). Willis (2007) describes this as a time when qualitative research realised that there was no universal truth to be discovered and that data collection and data analysis were not separate activities. This period also saw a rise in the importance of reflexivity. The fifth moment labelled the postmodern (1990-1995), is characterised as being a time when the separation between the researcher and the researched became blurred and an emphasis on story-telling arose. The sixth moment, post experimental inquiry (1995-2000), saw the development of a variety of creatively based methods of inquiry and reporting such as drama, conversation and performance. The methodologically contested present (2000-2010) is described by Denzin & Lincoln (2008) as the moment when multiple interpretive practices co-exist but Willis (2007) pointed out that this moment is also characterised by conflict arising from deciding upon criteria for publishing due to the development of a number of qualitative journals seeking criteria to set for publication. The future (2010-present), is labelled by Willis as methodological backlash and highlights the political context of qualitative enquiry and suggest that this period has seen the re-emergence of the primacy of post positivist type research. It is important to note though that each moment is not over or consigned to history. Each one still exerts influence and Denzin & Lincoln (2008 p.27) call this “an embarrassment of choice” in qualitative research that underscores the importance of clarity of choice when engaging in qualitative research.

They highlight that qualitative research is a relatively recent development in terms of research overall and suggest that the first moment is, the traditional, ranging from 1900-1950. At this time they argue, research was characterised chiefly by positivist philosophy and was dominated by quantitative designs. Anything else was considered to be not research. Following philosophical development however, qualitative research went through a period of identification concerned with differentiating itself from positivist research and locating is own philosophy and methodology. This second moment from 1950-1970 is called the modernist or golden age and contained the genesis of a variety of methods suited to conducting qualitative research. The rush of qualitative method development gave rise to cross pollination and this denoted the third moment defined as blurred genres (1970-1986). At this point it was suggested that a popular characteristic of the qualitative researcher was one of being a bricoleur, (Willis 2007). Denzin & Lincoln (2008) described a bricoleur as one who was able to be methodologically versatile and draw upon a range of methods to answer context specific questions. They caution however, that such borrowing runs the risk of compromising methodological integrity and consequently, the next moment is defined as Crisis of representation, (1986-1990). Willis (2007) describes this as a time when qualitative research realised that there was no universal truth to be discovered and that data collection and data analysis were not separate activities. This period also saw a rise in the importance of reflexivity. The fifth moment labelled the postmodern (1990-1995), is characterised as being a time when the separation between the researcher and the researched became blurred and an emphasis on story-telling arose. The sixth moment, post experimental inquiry (1995-2000), saw the development of a variety of creatively based methods of inquiry and reporting such as drama, conversation and performance. The methodologically contested present (2000-2010) is described by Denzin & Lincoln (2008) as the moment when multiple interpretive practices co-exist but Willis (2007) pointed out that this moment is also characterised by conflict arising from deciding upon criteria for publishing due to the development of a number of qualitative journals seeking criteria to set for publication. The future (2010-present), is labelled by Willis as methodological backlash and highlights the political context of qualitative enquiry and suggest that this period has seen the re-emergence of the primacy of post positivist type research. It is important to note though that each moment is not over or consigned to history. Each one still exerts influence and Denzin & Lincoln (2008 p.27) call this “an embarrassment of choice” in qualitative research that underscores the importance of clarity of choice when engaging in qualitative research. Using adult learning theory, (where adults are self directed and learn best when enabled to set their own learning outcomes), can create hidden tensions when the curriculum is professionally regulated.

Using adult learning theory, (where adults are self directed and learn best when enabled to set their own learning outcomes), can create hidden tensions when the curriculum is professionally regulated.

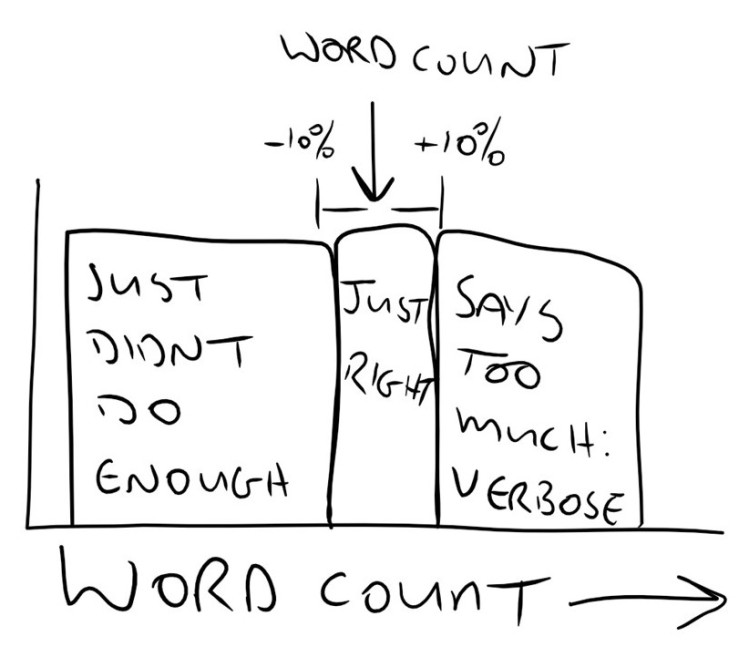

This seems fairly clear cut in the case of the underwriter. Not enough words usually leads to a sketchy answer but where do you draw the line with the overwriter? As a rule of thumb I advise my students and colleagues that I go +10% and then stop reading. The remaining overwritten piece can then be annotated as not read because it exceeds the word budget. Like the way Twitter does. Characters beyond the allowed limit are highlighted in red whilst Twitter waits for you to sort it out.

This seems fairly clear cut in the case of the underwriter. Not enough words usually leads to a sketchy answer but where do you draw the line with the overwriter? As a rule of thumb I advise my students and colleagues that I go +10% and then stop reading. The remaining overwritten piece can then be annotated as not read because it exceeds the word budget. Like the way Twitter does. Characters beyond the allowed limit are highlighted in red whilst Twitter waits for you to sort it out.